Written by Peter Piazza, a post-doctoral researcher at the Center for Education and Civil Rights, and originally posted at the School Diversity Notebook.

It’s been a little while since I wrote my last news roundup – I took some time off for summer, got a new job, etc, and, during that time, I was collecting stories about school diversity. There were a lot. I wrote about two big stories recently, comparing approaches to talking about race and school integration. Tomorrow, I’ll post links and short blurbs about some of my other favorite articles from the time I missed.

Sadly, my last news roundup was about a shooting in East Pittsburgh and, for this post, I want to focus again on Pittsburgh. Just weeks before the awful tragedy at the Tree of Life Synagogue, the NPR affiliate in Pittsburgh published an 8-part series looking at historical and contemporary struggles for school integration in the city, including a unique example of inclusion in the Squirrel Hill neighborhood.

Then, Andre Perry published this fantastic piece in the New York Times, connecting the Tree of Life shooting to school integration. Perry – a prominent school integration writer – grew up in Pittsburgh and went to integrated schools there. Here’s one of several powerful excerpts from his piece:

- “The fully integrated public school reflected the area’s diversity. I had history teachers who made connections between the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation Temple bombing in 1958 in Atlanta, and the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in 1963 in Alabama, solidifying for me how vulnerable black and Jewish communities are to white supremacy.”

Maybe the best description of how integrated schools are good for individuals and also have a much larger social purpose. A purpose that is especially important now.

As he notes in the article, Perry attended high school in 1988, which was also the height of statistical desegregation in the US, before schools began to resegregate. Pittsburgh is no exception to that general trend, although Pittsburgh – like virtually every city – has a very unique story re how segregation/desegregation/resegregation played out. And, that brings us to the series from Pittsburgh’s NPR affiliate, WESA.

I won’t take us through each part of the series, but you have full titles and links below. Each article is short, and you can also listen to the audio versions which are between 5-8 mins long. Here’s a quick overview.

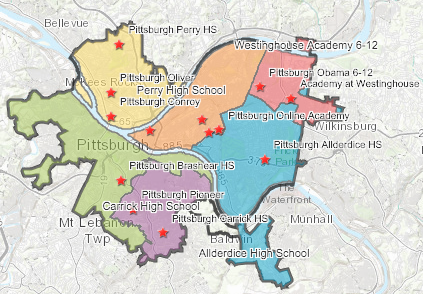

Before the WESA report, there was no publicly accessible map of Pittsburgh’s school feeder system (i.e., the system that shows which elementary schools send kids to which middle schools and so on). To find out where they were zoned, parents had to enter their address into an online search tool. Part 4 looks at how one family navigated this system. Using an open records request, WESA created the first ever map of the city’s current feeder system (see below). It’s an interactive map, and it also includes data on performance and student demographics.

(A quick plug – there’s a lot of variability in the ways that districts provide info to parents about school integration plans, attendance zones etc. On the whole, we don’t know much about what districts are doing and what is most effective, but we are currently working to compile this at the Center for Education and Civil Rights.)

The WESA series then focuses on different aspects of the feeder map, asking how it came to look the way that it does. Here’s a quick look at the history and major themes:

- 1964 – Pittsburgh used busing to move students out of majority-black schools and into majority-white schools; however, this was done to relieve overcrowding, not to achieve racial integration. Some of the earliest transfers went to schools in Squirrel Hill and, despite the many changes since then, 53 years later children in those majority-black neighborhoods still attend schools in Squirrel Hill.

- Pittsburgh neighborhoods were shaped by common racially discriminatory housing policies, like redlining and blockbusting, requiring busing to address overcrowding and, eventually, to facilitate racial integration. This is the focus of part 2.

- 1968 – Pittsburgh was ordered to desegregate by the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission, an 11-person board created to enforce the state’s anti-discrimination laws. But, it took a very long time to develop a plan. As described in part 3, the school board considered expanding busing, but “when that was even suggested, white parents went bonkers.”

- 1976 – Largely due to the backlash against even just the proposal of busing, white parents used their political power to switch Pittsburgh from an appointed school board to an elected school board, under the banner “Hell no, we won’t go.”

- 1977 – After multiple failed plans and much resistance, the Human Relations Commission asked state courts to intervene. The court then issued a desegregation order.

- 1980 – 12 years (!) after the 1968 desegregation order, a plan was finally approved by the school board; however, both black board members voted against it because it placed an unfair burden on majority black neighborhoods. The Human Relations Commission actually agreed with them; so, they rejected the plan and asked Pittsburgh to write a new one. BUT, Pittsburgh went ahead and implemented that plan anyway. Busing started that year and included roughly 11,500 students.

- 1996 – The desegregation era ended in Pittsburgh. Republican Governor Tom Ridge signed a bill that weakened the power of the Human Relations Commission, specifically preventing it from requiring that students be bussed for the sake of integration. The commission could make recommendations, but it could no longer enforce anything.

- 2005 – Pittsburgh closed 22 schools, largely due to declining enrollment. Part 6 of the series looks at how one closure affected its surrounding community.

- As in many cities, white families zoned to majority non-white schools use Pittsburgh’s school choice options to attend public schools outside their zone, or they transfer to private or charter schools (the topic of part 5). This has contributed to the city’s enrollment decline.

- And, it has cost the city a lot of money. When students attend schools outside their zone – even when students attend private and charter schools – the district (!) is on the hook for their transportation. Part 7 looks at transportation issues in the school system. As pointed out there, “in the 2012-2013 school year, 60 percent of the kids living in Pittsburgh went to a school other than their neighborhood school.” Transportation costs from that are massive, especially to a city already devastated by the loss of its iconic industries.

- 2012 – Pittsburgh’s school feeder map was adjusted to ensure that each elementary feeds to only one middle or high school.

- 2017 – The school board commissioned a study of the district’s demographics, including 10-year enrollment projections for public, charter and private schools. That report is expected any day now.

Unfortunately, that report will be delivered to a school superintendent who is no proponent of school integration. His public statements amount to the contemporary argument for separate but equal, that same tired argument you hear everywhere: instead of integrating schools, let’s make sure all schools are great. In his words, as quoted in part 8, it’s not segregation, but low expectations that is the main problem:

- “that’s the difference-maker to me, that we have high expectations for all students and meet them where they are,” he said. “Lift them up, then we’ll see equity begin to manifest itself in a more robust way in our schools.”

The report, however, could lead to major changes to Pittsburgh schools, including “opening schools, closing schools, changing feeder pattern lines or throwing the whole map out the window and letting parents choose which school to send their kids to,” as outlined in part 8. Without explicit attention to racial integration, none of this will help. At best, the “make all schools great” argument is misguided. It overlooks the fact that we could have done this a long, long time ago. It overlooks the fact that, even if we were to magically achieve equal schooling, we’d miss out on extremely socially important opportunities for contact and understanding across racial differences. And, on that note, I want to return to Perry, who ties it all together much better than I can:

- “Today the schools in Pittsburgh are less integrated than they were in the 1980s. That means there are fewer opportunities for teachers, or even students, to have meaningful discussions about the violence that is victimizing all of us. On Oct. 25, two black shoppers were killed in a Kroger supermarket, in Louisville, Ky. Two days later, 11 Jews were massacred at the Tree of Life synagogue. If our communities and schools are less integrated, less inclusive, how can teachers or anyone else hope to make the connections for us?”

Dividing Lines: The Shape Of Education In Pittsburgh

Overview: New WESA Series Takes A Closer Look At Where Pittsburgh Kids Go To School (1 min)

Part 1: What A Handful Of Streets On The Pittsburgh Public Schools Feeder Map Tell Us About Our Past (5 mins)

Part 2: Pittsburgh Neighborhoods And Schools Remain Segregated, But How Did It Start? (8 mins)

Part 3: An Unsuccessful 30-Year Effort To Desegregate Pittsburgh Public Schools (8 mins)

Part 4: Strange Shapes, Jagged Lines: The Patchwork Of Pittsburgh School Zones (5 mins)

Part 5: How School Choice Impacts Diversity At Pittsburgh Schools (5 mins)

Part 6: What Happens When A Neighborhood Loses Its School? (5 mins)

Part 7: Think Parkway Gridlock Is Bad? Try Commuting By School Bus (5 mins)

Part 8: Superintendent Hamlet On Improving Schools: ‘It’s Not A Sprint, It’s A Marathon’ (5 mins)

0 Comments