This was originally posted on The School Diversity Notebook by Peter Piazza at the Center for Education and Civil Rights at Penn State. We are very grateful for our partnership with Peter and for his work in this field!

I’m excited to feature a post from Dian Mawene, a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who recently published new research about a school rezoning effort in a diversifying Wisconsin suburb. Coauthored with Aydin Bal, the piece explores overlapping forms of segregation at the neighborhood, school district and school levels, all of which is anchored around a contentious effort in 2007-08 to shift attendance zone boundaries in the district. In the post below, Dian summarizes key themes from the published paper, and she connects those themes to a more recent rezoning effort (2017-18) that isn’t included in the article.

District-level attendance zone changes have enormous potential for school integration- they don’t require new laws or extensive amounts of new funds, and they fit comfortably within SCOTUS rulings that limit allowable remedies for school segregation. (Relatedly, CECR – who hosts this blog – is developing a database of attendance zone boundary changes over time, and they’re still looking for data from district leaders – check out the call here.) Like the town of Wells, WI featured below, suburbs across the country have been diversifying at a stunning pace. Of course, this carries major implications for schools. In Massachusetts, for example, we recently found that the share of “intensely segregated white schools” (>90% white) has dropped by 72% in the last 12 years.

At the same time, the Trump administration has weakened federal fair housing rules in an effort to preserve what the President calls the “Suburban Lifestyle Dream”. (Check out this podcast for clear/concise discussion of Trump’s attack on fair housing.) As described in an Ed Week article out today, this is a clear appeal to racialized fears of suburban voters, and it indeed makes the work of school integration so much harder. Both in her post and the larger article, Dian highlights the challenges that shaped the rezoning debate in Wells, and she points the way towards the (undeniably difficult) work of breaking the status quo that separates us.

A Tale of Two School Rezonings, by Dian Mawene (University of Wisconsin-Madison)

In my recent publication entitled “Spatial othering: examining residential areas, school attendance zones, and school discipline in an urbanizing school district” published in Education Policy Analysis Archives, my coauthor and I delved into structural factors that might contribute in racial discrimination in school disciplinary actions in Wells School District (WSD)* located in a vast growing demographically changing suburb in Wisconsin. Students of color, particularly African American students, in WSD have long experienced racial discrimination ranging from discrimination in special education identification—particularly in Emotional/Behavioral Disturbance (E/BD), school discipline, academic achievement, and graduation rate. Students of color experience multiple layers of segregation at the neighborhood level through segregated housing, school district thorough attendance zones policy, and school programs through special education and school discipline. What we found in the study is that racial discrimination in school discipline mirrors the existing segregation at neighborhood and school district. That is, African American and Latinx students have 3 to 22 times risk of being suspended, particularly in elementary schools where they are hyper-segregated, mirroring findings from related research on school discipline disparities.

For the purpose of this blog, I will pay particular attention to the complexities of redrawing elementary school attendance boundaries in the middle of racially and economically segregated neighborhoods. In the published paper, we utilized data from elementary school rezoning happened in 2007-08. In this blog, I will also include data from the most recent elementary school rezoning that took place in 2017-18. I utilize the instances of these two-consecutive redrawing of elementary school attendance zones in the hope of providing a comprehensive context for understanding the complexity of school and neighborhood segregation.

Despite the inevitable increase of diversity in race and class in Wells, long-term residents of the city have insisted on maintaining a long-standing aspect of the core identity of suburbia: homogeneity. Since their inception, the city and its school district have always assigned students to attend schools based on their residential area. Each elementary school was built to serve one section of the city (e.g., north side, east side, etc). With the increasing racial and economic diversity of the student population, community members and school district leaders are challenged by two competing options: maintain the principle of neighborhood public school, or work on equity in student distribution. With increasing neighborhood segregation, it seems difficult to achieve both agendas — neighborhood public schools and equity — simultaneously.

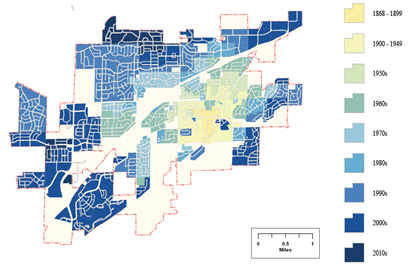

The city is divided by a highway that creates a natural boundary between enclaves of upper-middle class on one side of the highway (north and northwest side) and moderate to low income on the other side, particularly in the older part of the city that was once a general commercial strip. As housing developments continue to expand toward the periphery of the city (see the map below), housing prices in older buildings of the older Wells district have declined and the area has gradually become a housing market catering for people from low-income backgrounds. This area is where Cole Elementary School* is located. Cole Elementary is a school that has historically served most of the city’s minoritized population, possible as a result of spatial planning and practice.

Segregation of low-income housing, or what the locals call “pockets of low-income,” is partially a result of fair share policy adopted by the local county, which required all municipalities within the county to take on a share of the responsibility for low-income housing. Although it might seem that Wells, a type of upper middle-class white suburbia, accept people of color from low-income backgrounds, in reality people of low-income backgrounds and people of color are concentrated in the oldest and densest part of the city. These areas are less desirable for housing and economic developments than other parts of the city and have been designated as a blighted area. Unaffordable housing prices in other parts of the city exacerbate the concentration of “pockets of low-income”. The city also passed multiple ordinances, such as a discriminatory housing ordinance and a chronic nuisance ordinance, that prevent people from low-income backgrounds from moving into other parts of the city.

The challenge for the school district is to balance students by race and economic status across all elementary schools. In the account below, I compare instances of the two-consecutive redrawing of elementary school attendance zones.

The 2007-08 rezoning started with an acknowledgement that it was simply not right to have one elementary school – Cole Elementary—with 47% students from low-income backgrounds while the district’s average was 21%. School board and community members realized that reducing the concentration of students from low-income backgrounds was equally important as deciding which neighborhoods sent their children to which school. However, reducing the concentration of low-income students in Cole Elementary came with the risk of distorting the concept of a neighborhood school. The process of redrawing boundaries was contentious; families affected (i.e., families who would have to change schools) strongly opposed the change. At the end, the school district leadership was able to reduce the percentage of students from low-income backgrounds in Cole Elementary only from 219 students (47%) to 175 students (42%). They did it by re-districting middle-upper class students from an already overcrowded school district. The number was not sufficient to meaningfully balance the enrollment, but the decision was significant enough to have political consequences. The school board member advocating for equity lost in the next school board race. Despite the risk, the board member said it was “absolutely worth it.” The decrease of concentration of low-income students in Cole Elementary, however, did not last long. Starting the following year (See map above), the percentage began to steadily increase.

What happened? There were two potential causes: First, existing neighborhood segregation. It was difficult to balance student enrollment without first tackling neighborhood segregation. The attempt by the school board was bold but because of economically and racially divided neighborhoods, the effort fell short. Second, parents choose “with their feet”. A total of about 50 students from affluent neighborhoods in the north east side of the city were assigned to Cole elementary. This decision was made to reduce overcrowding at the more affluent neighborhood’s school, Eagle Elementary*, as well as to reduce the distribution of students from low-income backgrounds in Cole Elementary. Some students who attended Cole Elementary prior to the rezoning were assigned to attend Meadow Elementary*, a new school built in that year. In reality, after the decision was made, fewer than 20 children from Eagle Elementary actually attended Cole Elementary. Some of the students remained in Eagle Elementary for reasons of special education, while some students utilized the open enrollment option to go to other elementary schools within the district, and some others moved to private schools. People seemed to prefer to keep neighborhood attendance zones intact, and many may also have been reluctant to have their children assigned to Cole given its perceived socio-economic and spatial disadvantages.

Ten years later, in 2017-18, the school district built two new elementary schools; this time to serve new neighborhoods in the predominantly affluent side of the city (north and northwest). Equity was not a prime consideration in this rezoning. The school district leadership “restored” the original principle of neighborhood school by making boundaries between schools contiguous. School district leadership believed that it would be okay to have a concentration of students of low-income backgrounds and of color as long as they were not more than 50%. The school district failed to acknowledge that Cole’s percentage of students from low-income backgrounds was well above 50%, and other elementary schools were far below 50% (see the chart below). As a result of prioritizing neighborhood schools, the percentage of students from low-income backgrounds in Cole Elementary rose from 46% in 2017 to 57% in 2018 while the percentage of low-income students in Greenwood Elementary, one of the newly built schools, was only 11%. The most recent enrollment data (2019-20) show that Cole’s enrollment of low-income students is 65%, while Greenwood’s is 9.8%.

How could policy reverse the pattern of segregation noted in the study?

The problem is complex, and it is systemic. Therefore, the solutions need to be systemic as well. While there is no one single solution to the issue, there are some policy implications worth considering:

- Simply stated: the concept of neighborhood public schools does not go hand in hand with equity, unless neighborhoods are racially and economically diverse. When the rezoning committee opted to keep the neighborhoods intact, they automatically opted out of equity, meaning, in this case, a balanced distribution of students from low-income backgrounds, many of whom are students of color, across all elementary schools, or at least a reduction of the percentage and concentration of low-income students in Cole Elementary.

- Collective endeavors and boundary-crossing practices from city and district officials are needed in order to disrupt the status quo.

- The city needs to reconsider its location of low-income housing developments, and other city policies such as ordinances that (in)directly influence residents of color from low-income backgrounds to rent housing in areas perceived as “pockets of low-income”.

- The school district needs to acknowledge existing racial-class-spatial segregation that comes from the decisions about remaking school boundaries. This particularly pertains to the most recent rezoning. Policies that do not take into account racial-class-spatial realities may further marginalize minoritized students. Perhaps it is time to reconsider the neighborhood public school policy, or perhaps to redefine what neighborhood means.

From these two instances of rezoning, we can learn that there is a complex interplay between housing policies and practices, neighborhoods school concept, as well as city and school district leadership. When school district leadership is equity-oriented, it questions the notion of neighborhood public schools. On the other hand, when leadership does not take into account racial-class-spatial realities, it puts minoritized students at a disadvantage in order to maintain the concept of neighborhood schools.

*We used pseudonyms for the city and its schools because we are still conducting a qualitative study there and given the size of the city and its unique context, using real names might allow deductive breaching of the identities of people we interview in our ongoing study.

0 Comments