This is a cross-posting from The School Diversity Notebook. You can read the orignial version here. As always, we are so grateful for SD Notebook and Peter’s collaboration and generosity with his thoughts and reflections!!

#KnowBetterDoBetter Part II: A conversation among White parents, advocates & educators about school integration

This guest post is written by Katie Dulaney, a former middle school teacher in North Carolina. Katie is currently an advanced doctoral candidate in the Department of Education Policy Studies at Penn State University, where she studies how school districts instill and nurture commitments to equity.

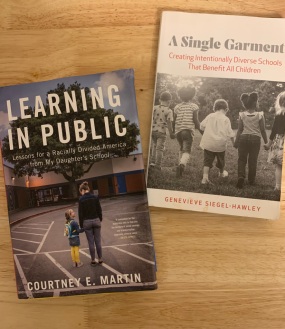

This post is part two in a three-part series in which three parents, advocates, and educators share reflections on the books A Single Garment by Genevieve Siegel-Hawley and Learning in Public by Courtney Martin. Karen Babbs Hollett’s post was published on January 24th and a forthcoming post will be written by Peter Piazza. This post focuses on aspects of external integration (i.e., how we secure diverse student populations within schools) and internal integration (i.e., what school structures and processes support school members’ ability to access the full benefits of diversity), from the perspective of a White woman who was an elementary student in an integrated magnet school and later, a middle school teacher at an integrated magnet school.

On Wednesday, February 2, at 4pm ET/1pm PT the Center for Education and Civil Rights at Penn State University (home of this blog) will host a virtual conversation between Siegel-Hawley and Martin, focusing specifically on the role White families and schools play in supporting racial integration. All are welcome, and registration is free here: https://tinyurl.com/CECRRegistration.

“To be clear, the bonuses derived from diversity don’t accrue automatically. It takes hard work for a diverse team (or school, or classroom) to cleave together and thrive. Cross-racial trust is a fundamental ingredient and, in a society grappling with the past and present effects of deep-seated discrimination, hard won” (Siegel-Hawley, p. 15).

There’s a magnetic bumper sticker on the side of my refrigerator that reads “Integrated Schools Benefit ALL Children.” I stuck it there years ago, when I was a new graduate student at Penn State. The word “ALL” is capitalized, written in red and underlined; someone clearly knew that if this sticker were traveling around on the bumper of a car as it was made to do, the word “ALL” would need to be emphasized most. As I stood making coffee this morning, Siegel-Hawley and Martin’s books fresh in my mind, I focused on and really pondered this bumper sticker for the first time in awhile. Have I always understood that point? Made choices in light of it? Taught it?

I’ll preface by saying that my answers to these questions are informed by a decision my own parents made on my behalf – to enroll me in a racially integrated magnet school. They’re also largely shaped by my experience as a teacher of four years in an integrated magnet middle school whose student population, when I was there, was 1/3 Latinx, 1/3 Black, and 1/3 White. My parents have always explained the decision to send my brother and me to our elementary school by sharing that they trusted the principal (who, perhaps not coincidentally, was a White woman with a doctorate) and that the classrooms just felt comfortable. My mom liked that they had rocking chairs and dress-up materials. She admired the school’s magnet theme of communication. My parents acknowledge that by the time they were looking at schools, they had adopted a number of child-centered practices from the cooperative pre-school my brother and I attended. Chief among these practices was the routine of holding family meetings. Every month or so, my parents, brother, and I would collectively discuss our needs and concerns, negotiate our responsibilities in a way that felt fair, make agreements with one another, and sign our meeting minutes to signal our consent. We started this practice when my brother and I were young enough to still be signing our names with backward letters. Point being, communication was an attractive theme to my parents.

Teaching in a magnet middle school helped me think more critically about the strategy involved in achieving integration and the effort that schools and teachers have to exert, oftentimes to reel White families in. The choice of a theme, for instance, should be strategic. I taught in a Montessori middle school. Siegel-Hawley talks about attending Binford Middle School in her book, which was a magnet school with an arts focus. I’ve come to understand that marketing efforts are themselves generally biased toward White families — particularly if they’re coming from schools with a progressive theme — because they tend to highlight abstract, non-academic values: play, freedom, social emotional learning, experiences in nature, hands-on learning. As a teacher, my colleagues and I would staff a rotation at the magnet fair each year where we, too, “marketed” our school to prospective families. Knowing what I now know, I’m certain that the rocking chairs and play stations my mom was so enamored by were intentionally placed as part of a larger marketing effort on the school’s part — they were highlighted on tours in order to convince parents like my own that they could trust the school with their children because their values would be reflected in this space. And these touches clearly worked. The dress-up center was a progressive detail that signaled “child-centered education.” The rocking chairs offered a hint of “gentle,” a draw that Karen reflected on in her last post and that White parents in Martin’s story were so in search of.

As a theme, “communication” not only appealed in an abstract sense to a progressive audience; it also had practical value in a school that sought to gather families of disparate races and ethnicities together. As elementary students, my brother and I helped run a televised news show in the mornings. We were part of a ham radio club after-school. We also witnessed low-stakes but memorable conflict between families of different races as they sought to make sense of their differences. I distinctly remember my mother struggling, on multiple occasions, to understand why my second-grade teacher, a Black woman I respected and admired, chose to discipline our class in the ways that she did. My mom found her style of management to be abrasive. In one instance, my teacher disciplined our class after an especially unruly day by withholding a treat that the PTA had purchased for all students. My mom was PTA treasurer at the time, and she’d spent a lot of time purchasing whatever this treat was and making sure it was distributed to each classroom. She was frustrated that the treat was taken away as a punishment, but I suspect her frustration was rooted in a lack of trust in my teacher. If trust were established, she would have respected my teachers’ judgment or at the very least, taken her concerns to my teacher herself. Instead, she took her frustration to the White principal. The next morning, our teacher handed out the treat.

I remember understanding, at least in part, both sides of this disagreement as a kid, and I think I understood this precisely because I was a student in an integrated school. I had a relationship with my teacher and my mom that they didn’t have with each other. I saw my Black teacher as a respected professional, and I knew and loved my White mom. It’s not lost on me that I attended a communications school and yet, in instances like these, deeper conversations about cross-racial trust were not broached head-on. Though I wouldn’t have used words like “lost opportunity” in elementary school, it’s what I grew up to think. External integration was achieved in my elementary school thanks to our diverse student population, but we lacked some structures, like communication norms and a space for dialogue, that could have helped us achieve a deeper level of internal integration. The need for these structures was especially important because spaces of integration weren’t common in my community; there weren’t existing relationships and norms that teachers and parents connected to our integrated school could readily draw on.

I’m not naïve enough to think that internal integration is easily achieved, and I struggled to have these conversations in my own right as a teacher. A number of times, I am sure I was the White teacher that a parent of color had misgivings about. I can now appreciate why families of color may enter schools wondering if they and their children will be valued, fully included, and respected but as a teacher in my early twenties, I didn’t have enough context to depersonalize that dynamic. In one instance, a Black student in my class had gotten a failing grade on an assignment that he hadn’t yet turned in. His mom was skeptical; she seemed worried that I’d misplaced the assignment or overlooked it entirely. The parent called a conference, pulled her son from his class, and had him pull out every assignment from the entire quarter from his notebook and backpack and line it up against my grade book. We were crunching numbers at my planning table. Multiple times, the student’s parent asked me to explain, point by point, my grading decision on a given assignment. It was a long meeting, and it felt very tense. I think I knew then that this mom was trying to protect her son from what she feared was bias—perhaps influenced by interactions with other White educators or by what could have been daily encounters her family experienced— but I also did nothing to try to reframe the conversation. Instead, I pulled up the gradebook and covered my bases. I was determined to prove myself as a professional, to protect my own sense of worth. I didn’t understand, then, that this was about trust; that I hadn’t done enough yet, as a White teacher, to earn the trust of this family; and that the slow, intentional work that goes into building relationships between teachers and families across color lines did not look like this. It did not involve sitting at opposite ends of the table arguing about grades.

These stories, of course, aren’t really about treats from the PTA or making sure every assignment is properly accounted for. They’re about how trust is forged across color lines, particularly between teachers and parents. They’re just two examples, though wholly unequal, of a White parent asking a Black teacher, of a Black parent asking a White teacher: do you understand how special my kid is? Can I trust you to take care of the most important person in my life? Knowing what I now know, I wish I could go back and facilitate some conversations that were never had. I wish I could reframe some conversations that were had. As Martin shares in her own writing, these conversations are challenging. My teacher preparation program didn’t teach me how to initiate them, nor did it prepare me to be on the receiving end of them. Martin’s own account of wading into these discussions left her feeling “Off-center. Porous. Overwhelmed” (p. 186). Yet the practice of having these conversations, even when we get them wrong, makes way for a kind of understanding that I think we desperately need right now. And if we are going to “cleave together and thrive,” as Siegel-Hawley’s opening quotation challenges us to do, we would be wise to “show up…stay put… and keep talking about it” (Martin, pp. 131, 186). Our virtual conversation this Wednesday, February 2nd is an opportunity for us to practice these skills in community. Please join us and include your voice.

0 Comments