This is a cross-posting from The School Diversity Notebook. You can read the orignial version here. As always, we are so grateful for SD Notebook and Peter’s collaboration and generosity with his thoughts and reflections!!

#KnowBetterDoBetter: A conversation among White parents, advocates & educators about school integration

This guest post is written by Karen Babbs Hollett, a former teacher, instructional leader, and director at a state department of education. Karen is currently an advanced doctoral candidate in the Department of Education Policy Studies at Penn State University, where she studies issues of racial equity in early care and education (ECE) policy. Following the murder of George Floyd, American public schools were pressed to take a look at their role in systemic racism and invest in new diversity and equity initiatives. And then, well, you know what happened next. Nationally, conservative political leaders have hijacked efforts by schools to be more culturally affirming, pitching them as the boogeymen that will teach White children to hate themselves and their country. As last fall’s election results in Virginia showed, this strategy worked. White parents, advocates, and educators need to push back on this narrative, and two recent books – and a related event – provide both the information and the perspective to do so.  A Single Garment: Creating Intentionally Diverse Schools That Benefit All Children, by Dr. Genevieve Siegel-Hawley, explores the leadership, policies, and practices that support contemporary school integration in four Richmond, Virginia schools. Drawing on a wide range of sources – including her own experiences as a former White student and teacher in Richmond schools and a current mom of White kids living in Richmond – she provides a richly layered account of how each school approached achieving racial integration as a foundation for a just, democratic society. What’s especially impressive about the book is Siegel-Hawley’s ability to stitch together loads of historical and academic content with compelling real-life case studies and poignant personal anecdotes, without the book ever feeling winding or heavy. It’s an accessible read, with a really persuasive argument.

A Single Garment: Creating Intentionally Diverse Schools That Benefit All Children, by Dr. Genevieve Siegel-Hawley, explores the leadership, policies, and practices that support contemporary school integration in four Richmond, Virginia schools. Drawing on a wide range of sources – including her own experiences as a former White student and teacher in Richmond schools and a current mom of White kids living in Richmond – she provides a richly layered account of how each school approached achieving racial integration as a foundation for a just, democratic society. What’s especially impressive about the book is Siegel-Hawley’s ability to stitch together loads of historical and academic content with compelling real-life case studies and poignant personal anecdotes, without the book ever feeling winding or heavy. It’s an accessible read, with a really persuasive argument.

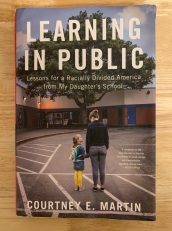

- Learning in Public: Lessons for a Racially Divided America from My Daughter’s School, by Courtney E. Martin, chronicles the story of Martin enrolling her daughter in a local public school in Oakland, California. Martin examines her own fears, assumptions, and conversations with other parents as they navigate school choice, providing a vivid portrait of integration’s virtues and complexities. In particular, she tackles head-on the gap between what White progressives espouse regarding diversity and equity for families of color and what they actually do when it comes to their own children. Similar to Siegel-Hawley’s book in its clarity and accessibility but distinct in its genre as a memoir, Martin’s honesty and willingness to call out both herself and her White friends pushed me to reflect in new ways on my own contradictions as a White mom committed to racial equity.

On Wednesday, February 2, at 4pm ET/1pm PT the Center for Education and Civil Rights at Penn State University (home of this blog) will host a virtual conversation between Siegel-Hawley and Martin, focusing specifically on the role White families and schools play in supporting racial integration. All are welcome, and registration is free here: https://tinyurl.com/CECRRegistration. This #KnowBetterDoBetter blog post series (inspired by Courtney Everts Mykytyn of Integrated Schools) will feature a conversation about school integration among three White advocates who are also parents and former classroom teachers. We will reflect on how the books and related event shape our work in education, as well as our personal choices. Peter Piazza and Katie Dulaney will respond to this initial post. We invite readers into the conversation as well, either in comments here, on Twitter, or at the event. To start, this post focuses on the role parents can play in advancing racial integration and equity in schools. Both Siegel-Hawley and Martin are moms, and their books both share first-person accounts of their questions and struggles as White parents trying to do their part in making schools more integrated, equitable, and just. While that is the central story of Learning in Public, it’s also a thrust of A Single Garment. Siegel-Hawley even opens her book with a letter to her young daughter. Siegel-Hawley’s and Martin’s stories were ones I needed to hear this year as I’ve grappled with what feels like the end-all decision of where to send my four-year-old daughter, Lillian, to school. Had you asked me two years ago which school she’d attend, I would have, without hesitation and perhaps with a hint of self-righteousness, said her local public school, of course. But then the pandemic hit, Lillian’s preschool closed, and when her brother was born in May of 2020 my husband and I decided to pull her out of preschool long-term in order to keep his little infant immune system safe. She returned to preschool this past September, and the transition was tough. Compared to our little cocoon of a home, preschool was loud and chaotic. She didn’t remember how to make friends. It was just too much, she said. By November, I started to worry that kindergarten would be too much, too. I recalled the story in chapter 37 of Learning in Public when a friend of Martin’s toured 15 elementary schools but reported that, “Nothing felt quite, well, gentle, you know?” That’s what I wanted for Lillian. I wanted gentle. I wanted a kindergarten that would give her the 1.5 years of preschool she lost in the pandemic, that would help her ease back into a world of noise and bustle and other people. I decided to tour a private school that had a reputation for what I took as gentleness. It was the kind of school that had stuffed animals in the classroom and little yoga mats tucked underneath each chair, and refused to administer standardized tests. At an open house for the school, I chatted with two parents of other students – both White – while Lillian glued beads on a pinecone. When I asked about the racial and economic composition of the student body, I was assured that diversity was a priority, and that scholarships were set up for that, but that it remained an “area of growth” for the school. In that moment, I felt like I could be an anecdote in Learning in Public. I won’t trouble this post with more details of my White progressive soul searching, but to summarize, I understand the conflicts Martin elucidates in her book. I get how one parent could claim, “You have to separate your ideology from your parenting. It’s not the same” and how another could confess to the “cognitive dissonance” she felt after choosing to enroll her child in an expensive private school instead of the public school in her Oakland neighborhood. And at the same time, they remain excuses that need to be troubled, especially by other White parents. Martin does this. And while Learning in Public captures many other parts of her family’s story – the amazing academic and social growth her daughter makes in a racially integrated public school, the clumsy mistakes she and other White families make in their attempts to be allies – her examples of how a White parent can question and prod other White parents about schools are particularly valuable, especially as schools are increasingly becoming the arenas in which political debates are being decided. After making the commitment to send Lillian to public school, I have vowed to funnel my White middle-class maximizer mom tendencies toward learning more about the extent to which true racial integration exists in our district, and figuring out what I can do to support it. I should be clear about where my family lives – it’s not Richmond or Oakland or any of the other communities I typically think of as being on the front lines of racial integration efforts. It’s State College, Pennsylvania, a small city in the middle of the state that surrounds Penn State University. While State College is far more racially and ethnically diverse than its surrounding rural counties, it’s still predominantly White. Indeed, the most racially diverse elementary school in our district is still 59% White. Our zoned public school is 80% White. What, then, does racial integration look like here? A Single Garment provides a comprehensive look at what racial integration entails, and helped me understand what it can mean in a district like mine. Specifically, as Siegel-Hawley explains, racial integration is not just achieving schools with demographic distributions that are more even, it’s about ensuring that the children of color in those schools have equal, and in some cases greater, access to key educational resources like experienced teachers and rigorous and culturally affirming curricula. True racial integration also means that school policies and practices that can cause segregation within schools, like tracking and exclusionary discipline, are monitored closely and redesigned as needed. These factors, what Siegel-Hawley calls “internal integration,” give me as a parent things to look for. For example, I can look at who is and is not represented in the books in Lillian’s classroom, and more specifically, whether the contributions of people of color are described outside of the context of their oppression (e.g., are the only Black Americans she learns about Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks?). I can ask what school leaders, including the principal and PTO, have done to make the school welcoming to families of color, especially since just a few blocks away from our zoned school is a charter school that is far more racially diverse. What are they doing to attract families of color that our zoned school is not? Or I can ask why all – literally, all – of the teachers at the school are White, and what can we do about that? Put simply, as a White parent, I can ask questions about and advocate for the resources and experiences that will support not just the few children of color in Lillian’s school, but everyone. This is a point Siegel-Hawley emphasizes: White children stand to gain just as much from diverse schools as students of color do. And what would Lillian get from equal-status interactions with classmates of color? According to the research Siegel-Hawley presents, a whole lot – improved language development, enhanced critical thinking, greater development of empathic reasoning, greater likelihood of cross-racial friendships later in life, and more. And when I think about what I really want for my daughter, not just for her kindergarten year but in the long term, I’ll easily give up “gentle” for that.

0 Comments